Way #3

Resolving Conflict Tenderly

Win-Win Sweethearts

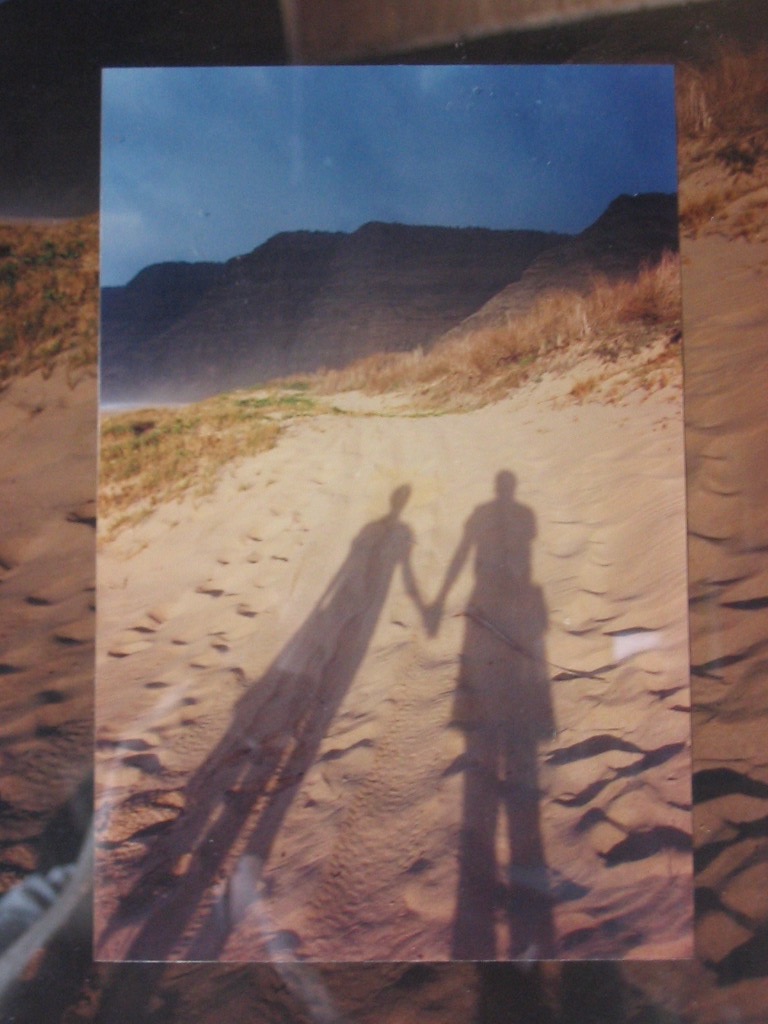

Allwin and Nonelose were sweethearts

And what a sweet couple they were

They lived for each other’s happiness

And you could just hear their hearts purr

Naturally they had their quarrels

Two won’t always feel as one

But they took care to resolve them

So they would both feel that they won

The first step was banishing all blame

Admitting they each played a part

In creating the conflict that faced them

And made them feel slightly apart

The next thing they’d do is acknowledge

The feelings that each of them felt

Especially their hurts and their fears

To cause their defenses to melt

Then they would make sure each other

Felt their point of view was as good

As the point of view held by the other

Respecting where each of them stood

Finally, they’d explore their options

But before they would even begin

They’d agree that their primary goal

Was to make sure that they both would win

In time they grew closer and closer

And they felt increasingly smart

For using their conflicts as chances

To tenderly live heart to heart

(THE NEXT FOUR PAGES ARE PRINTABLE FOR YOUR USE:)

- OUR GOAL IS TO RESOLVE CONFLICT TENDERLY

- THE SAVE PROCESS SUMMARIZED

- THE SAVE PROCESS EXERCISE, PAGE 1

- THE SAVE PROCESS EXERCISE, PAGE 2

Click here to continue to these four pages.